Aerospace design starts with a clear mission and strict rules for safety, performance, and certification. Every aircraft or spacecraft must do exactly what it’s designed for carry a set payload, travel a specific distance, and operate safely under defined conditions. These aren’t flexible goals; they are fixed limits that determine whether a design succeeds or fails.

Meeting these requirements ensures the vehicle performs safely, efficiently, and can be certified for flight. Missing even one can cause costly redesigns, long certification delays, or in severe cases, complete mission failure. In aerospace, every component must work perfectly under extreme conditions—there’s no room for error.

Today, optimizing design within these limits is a competitive edge, not just a compliance task. This guide covers the key aerospace design requirements from mission goals and structural strength to regulations and sustainability. You’ll also learn the biggest design challenges, how optimization helps balance trade-offs, and how tools like BQP support faster, safer, and more efficient design workflows.

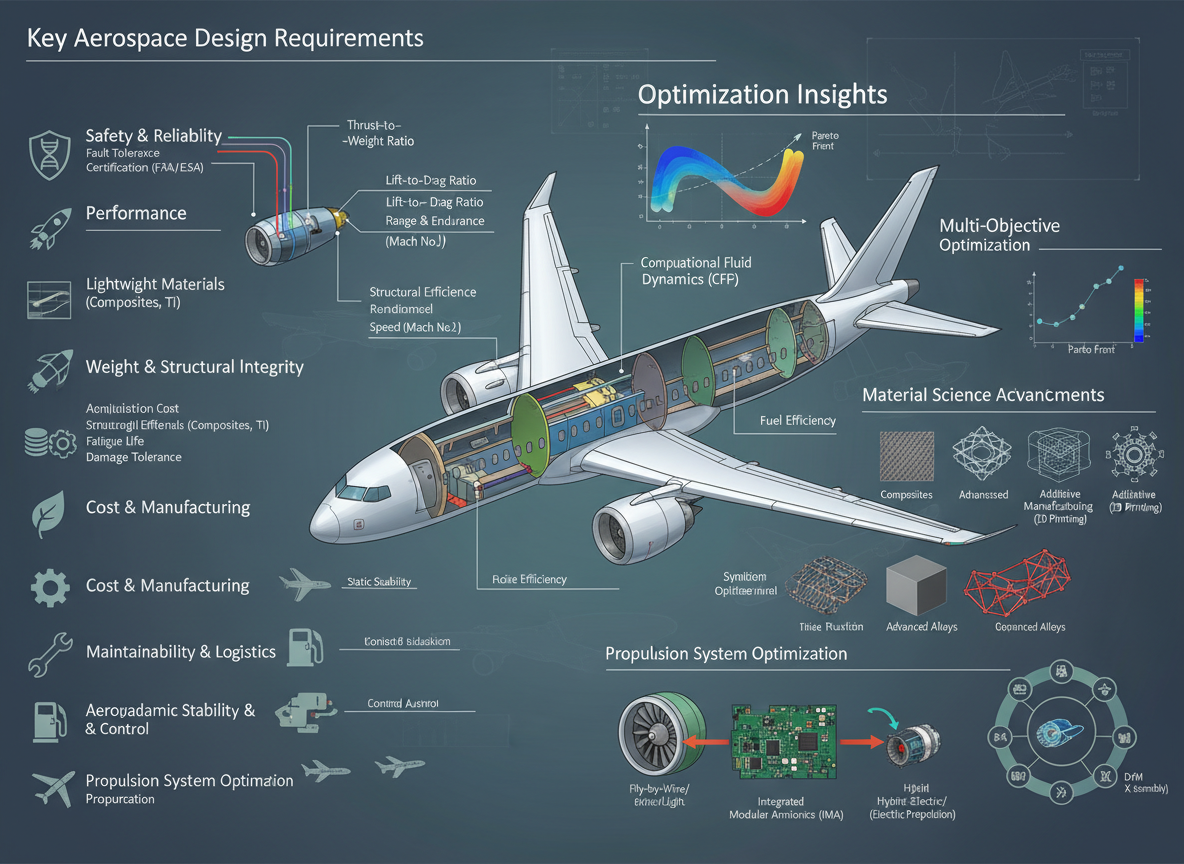

Common Aerospace Design Requirements

Aerospace programs must meet a mix of technical, safety, and regulatory requirements. These rules cover how an aircraft or spacecraft performs, how strong it is, how safe it must be, and how it affects the environment.

All these factors must work together improving one often affects another. Modern design tools help engineers balance these trade-offs early, reducing costly redesigns later.

Common Aerospace Design Requirements

Aerospace design requirements span multiple engineering disciplines, each with specific standards and validation methods. Modern programs must satisfy all requirements simultaneously rather than optimizing one at the expense of others.

Mission Definition & Performance Criteria

Every aerospace design starts with a defined mission — what the aircraft or spacecraft must carry, how far it must go, how fast it should travel, and under what conditions it must operate.

For example:

- A cargo aircraft prioritizes payload capacity and fuel efficiency.

- A fighter jet focuses on speed and maneuverability.

- A surveillance drone values long endurance and sensor stability.

These mission goals translate into measurable performance targets such as:

- Lift-to-drag ratio (L/D): Affects aerodynamic efficiency and range.

- Climb rate: Impacts takeoff and operational flexibility.

- Fuel efficiency (SFC): Determines range and overall cost.

Engineers also define threshold values (minimum requirements) and objective values (target goals). Reaching these objectives ensures the aircraft performs competitively within its class.

Design teams must balance speed, range, and payload improving one often reduces another.

- More speed usually means higher fuel use.

- Longer range requires more fuel, which adds weight.

- Larger payloads reduce range or climb performance.

Understanding these trade-offs early helps teams avoid pursuing designs that look ideal on paper but fail in real-world performance or economics.

Mission Definition & Performance Criteria

Every aerospace design starts with a defined mission — what the aircraft or spacecraft must carry, how far it must go, how fast it should travel, and under what conditions it must operate.

For example:

- A cargo aircraft prioritizes payload capacity and fuel efficiency.

- A fighter jet focuses on speed and maneuverability.

- A surveillance drone values long endurance and sensor stability.

These mission goals translate into measurable performance targets such as:

- Lift-to-drag ratio (L/D): Affects aerodynamic efficiency and range.

- Climb rate: Impacts takeoff and operational flexibility.

- Fuel efficiency (SFC): Determines range and overall cost.

Engineers also define threshold values (minimum requirements) and objective values (target goals). Reaching these objectives ensures the aircraft performs competitively within its class.

Design teams must balance speed, range, and payload — improving one often reduces another.

- More speed usually means higher fuel use.

- Longer range requires more fuel, which adds weight.

- Larger payloads reduce range or climb performance.

Understanding these trade-offs early helps teams avoid pursuing designs that look ideal on paper but fail in real-world performance or economics.

Aerodynamics & Aeroelasticity

Aerodynamics defines how an aircraft moves through air — how much lift it generates, how much drag it produces, and how stable it remains across its flight envelope.

Good aerodynamic design ensures efficiency and control. The wing planform, airfoil shape, and control surface size determine how the aircraft performs. Poor aerodynamic decisions early in design are costly to fix later since they affect structure, weight, and even manufacturing.

Key aerodynamic goals include:

- High lift-to-drag ratio for better fuel efficiency and range

- Stable control response across speeds and altitudes

- Low drag to minimize fuel burn and improve endurance

Aeroelasticity adds another layer of challenge — it studies how aerodynamic forces interact with flexible structures. Uncontrolled interactions can cause dangerous effects such as:

- Flutter: Rapid oscillation that can destroy a structure in seconds

- Divergence: Structural deformation that increases aerodynamic loads uncontrollably

- Control reversal: Control inputs producing the opposite of intended movement

These risks are prevented by analyzing and testing the aircraft under every flight condition.

Validation follows a proven sequence:

- CFD analysis to model airflow and pressure distribution

- Wind tunnel testing to confirm predictions at scale

- Flight testing to verify behavior in real conditions

Together, these steps ensure aerodynamic performance, safety, and stability — from the first concept to final certification.

Weight, Balance & Material Optimization

Weight is one of the most critical factors in aerospace design. Every extra kilogram reduces payload, shortens range, or increases fuel use. Managing weight effectively is the difference between a design that meets its mission goals and one that fails certification or performance tests.

Design teams maintain detailed weight budgets, dividing total mass among major categories:

Weight and balance influence the center of gravity (CG), which determines stability and control. A forward CG may improve stability but require more lift (and fuel). A rearward CG improves efficiency but risks control instability. Engineers must keep the CG within limits throughout the mission.

Material selection also plays a central role. The goal is to balance strength, durability, manufacturability, and cost:

- Composites: Excellent strength-to-weight ratio but difficult to repair.

- Aluminum: Easy to machine and affordable but heavier.

- Titanium: High strength and heat resistance but expensive and hard to fabricate.

Each choice locks in long-term implications for cost, maintenance, and lifecycle performance. Early weight and material optimization ensures the aircraft meets its mission requirements without exceeding budgets or certification limits.

Propulsion & Power Systems

Propulsion and power systems determine how an aircraft performs, how efficiently it operates, and how safely it responds under failure conditions. Engine design affects every performance metric — from thrust and climb rate to range and endurance.

Key performance targets include:

- Thrust-to-weight ratio: Determines acceleration and climb capability.

- Specific fuel consumption (SFC): Measures fuel efficiency over time or distance.

- Redundancy: Ensures continued flight if one engine fails, as required by safety standards.

Thermal management and fuel delivery are also mission-critical. Engines generate extreme heat, which must be controlled to avoid damaging nearby systems. Fuel must flow reliably at all altitudes, temperatures, and flight attitudes including during high-g turns or negative-g conditions.

As aviation shifts toward sustainability, new propulsion technologies introduce new challenges:

- Hybrid-electric systems add efficiency but require heavy batteries, reducing payload.

- Hydrogen propulsion offers zero emissions but demands cryogenic storage or high-pressure tanks.

- Fuel cells improve efficiency but increase system complexity and cost.

These new systems require integrated optimization across propulsion, structure, and thermal design. Traditional engines could be treated as separate subsystems; emerging propulsion concepts must be co-designed from the start to balance performance, weight, safety, and environmental impact.

Safety, Reliability & Regulatory Compliance

Aircraft and spacecraft must comply with strict safety and regulatory standards. Certification authorities like the FAA, EASA, or MIL-STD require proof that every system functions safely under all expected conditions. Compliance is non-negotiable failing to meet standards can halt programs or endanger lives.

Key steps for compliance:

- Analysis: Mathematical models predict performance and identify potential failures.

- Ground testing: Validates components and systems under controlled conditions.

- Flight testing: Confirms the complete vehicle performs safely across its operational envelope.

Critical systems require redundancy and reliability. For example:

- Dual or multiple hydraulic lines prevent total system failure.

- Backup electrical buses maintain essential power.

- Redundant flight controls ensure safe handling in emergencies.

Certification also extends beyond hardware. Personnel and process compliance are required:

- Pilots must have type-specific licenses.

- Mechanics need proper certifications (A&P).

- Manufacturing processes require quality approvals (DOA, POA).

By integrating safety, reliability, and regulatory compliance into the design from the start, aerospace teams minimize risk, reduce costly redesigns, and ensure mission readiness.

Environmental & Lifecycle Requirements

Modern aerospace designs must meet environmental and sustainability standards throughout the vehicle’s life. Regulations govern emissions, noise, and materials impact:

- Emissions: ICAO Annex 16 and EPA standards limit CO₂, NOx, and other pollutants.

- Noise: Aircraft must comply with acceptable decibel levels to reduce community impact.

- Lifecycle impact: Designs should consider manufacturing, operation, maintenance, and end-of-life recycling.

Key considerations:

- Manufacturability: Can the aircraft be built efficiently and consistently at scale?

- Maintainability: Can inspections and repairs be done economically over its life?

- Recyclability: Are materials recoverable, minimizing landfill waste?

Reliability across environments is critical:

- Avionics must operate from -55°C to +85°C.

- Structures survive vibration, shock, humidity, and salt exposure.

- Components endure extreme temperatures, acoustic loads, and other harsh conditions.

Environmental and lifecycle optimization ensures long-term efficiency, reduces operational costs, and helps programs stay compliant with evolving regulations.

Challenges in Meeting Aerospace Design Requirements

Real-world aerospace design confronts obstacles that complicate even sophisticated engineering approaches. Understanding these challenges helps teams build practical solutions.

- Balancing structural performance and weight: Lighter structures save mass but reduce safety margins. Advanced materials may offer performance benefits but often have limited operational history. Optimization must balance minimum weight with acceptable risk.

- Managing certification complexity: Certification requires extensive documentation and repeated updates. Every design change triggers analysis, test revisions, and paperwork, potentially causing long program delays.

- Integrating new materials and propulsion technologies: Legacy regulations were not written for composites, additive manufacturing, or hybrid-electric/hydrogen systems. Approval for new tech requires extensive coordination, slowing innovation.

- Ensuring reliability in extreme conditions: Aerospace systems must work from arctic cold to desert heat, from sea level to stratosphere, through turbulence and icing. Testing all scenarios is impossible, so designs must predict behavior confidently.

- Keeping pace with evolving environmental and sustainability mandates: Standards for emissions, noise, and lifecycle impact continuously tighten. Designs must anticipate stricter future regulations to avoid major redesigns.

Optimizing Design for Performance and Compliance

Effective optimization approaches balance all requirements simultaneously rather than optimizing sequentially and hoping constraints are satisfied.

- Use multi-objective optimization: Balance performance, weight, cost, and safety simultaneously. Pareto frontier exploration shows trade-offs, helping decision-makers select configurations that best meet program priorities.

- Employ digital twin simulations: Test thousands of mission scenarios virtually before building hardware. Identify edge cases and optimize for robustness across realistic conditions, not just nominal performance.

- Apply aero-structural coupling: Evaluate aerodynamic and structural trade-offs early. Integrated analysis prevents designs that are excellent aerodynamically but structurally infeasible, or vice versa, ensuring globally better solutions.

- Use surrogate and parameterized modeling: Replace time-consuming high-fidelity analysis with fast surrogate models. This allows exploration of thousands of design variations before committing to detailed analysis.

- Integrate certification considerations early: Build regulatory and certification requirements into optimization from the concept stage. This reduces expensive late-stage rework and ensures designs meet performance and compliance targets efficiently.

How BQP Enables Optimized Aerospace Design

Traditional aerospace design often optimizes subsystems sequentially, hoping the full system works when integrated. Modern complexity demands a more integrated approach. BQP provides cross-domain, quantum-inspired optimization for aerospace design.

What BQP Offers:

- Quantum-inspired optimization: Handles multi-objective, multi-constraint problems efficiently. Explore thousands of variables and hundreds of constraints to find better configurations faster than traditional methods.

- Digital twin integration: Validate designs virtually before physical testing. Test against mission requirements, environmental conditions, and failure scenarios to catch issues early when fixes are low-cost.

- Hybrid optimization workflows: Combine quantum-inspired global search with classical local refinement. Achieve faster convergence to superior design solutions.

- Cross-domain modeling: Link aerodynamics, structures, propulsion, and certification variables. Optimize all disciplines simultaneously rather than sequentially to capture interactions often missed in traditional approaches.

- Simulation-to-certification pipelines: Generate certification analysis and documentation directly from optimization results. Reduce manual rework and ensure consistency between design and compliance evidence.

Ready to optimize your aerospace designs?

Contact BQP to explore how quantum-inspired optimization can help your team meet all design requirements while improving performance, reducing weight, and accelerating certification.

Conclusion

Meeting aerospace design requirements is both a technical and strategic challenge. Engineers must balance multiple competing objectives performance, weight, cost, and safety simultaneously, leaving little room for error. Every decision impacts the overall mission, making integrated optimization essential.

Optimization-driven design goes beyond mere compliance. It ensures safety while improving performance, reducing lifecycle costs, and supporting sustainable operations. By evaluating trade-offs systematically, teams can achieve better results than traditional sequential approaches.

BQP’s quantum-inspired solutions empower aerospace teams to explore design spaces faster, validate against certification standards, and achieve mission success with fewer iterations. This approach reduces risk, accelerates development, and turns complex design challenges into actionable advantages.

FAQs

What defines aerospace design requirements?

They are performance, structural, and regulatory criteria. Mission requirements define what the vehicle must do, structural requirements ensure it survives loads, and regulatory requirements prove it is safe.

How are these requirements verified?

Through analysis, ground testing, and flight testing. Authorities like the FAA or EASA review all evidence before granting type certificates.

Why is optimization crucial in aerospace design?

It balances performance, weight, cost, and reliability while meeting constraints. Optimization finds the best trade-offs faster than manual design.

Can digital twins improve compliance?

Yes. They simulate tests virtually, identify edge cases, and reduce physical testing time and cost.

How does quantum-inspired optimization help aerospace design?

It efficiently explores large design spaces, handling thousands of variables and constraints to find better solutions faster than classical methods.

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)