Engineering optimization finds the best design from thousands or even millions of possibilities. Traditional methods work for simple, smooth problems, but real-world challenges often involve sudden changes, yes/no decisions, conflicting goals, or complex constraints.

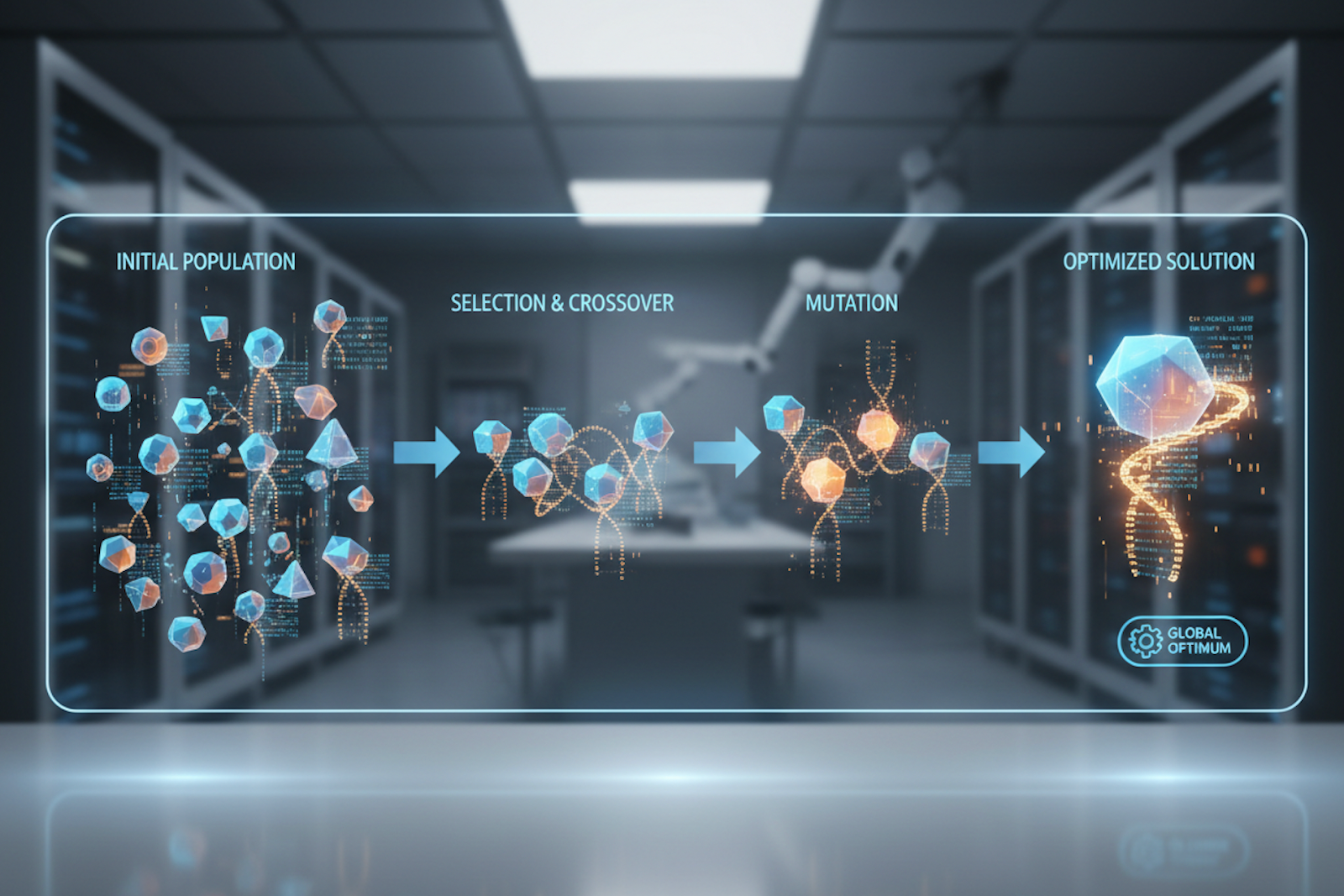

Genetic algorithms (GAs) tackle these by mimicking natural evolution. Candidate solutions compete, combine successful traits through crossover, and introduce small random mutations. Over generations, the population improves without needing smooth functions or gradients.

Recent studies show Genetic Algorithms reach optimal fitness values in at least one generation for tested problems. Hybrid approaches perform even better-one achieved a 38.87% improvement in compression ratios over conventional methods.

GAs are widely used in aerospace design, manufacturing schedules, control systems, and logistics especially when options are vast, goals conflict, or traditional methods stall.

What Are Genetic Algorithms?

Genetic algorithms (GAs) are search methods inspired by natural evolution. Instead of testing one solution at a time, GAs work with a population of candidate solutions that evolve over generations through selection, crossover, and mutation.

Each solution is represented as a "chromosome" that encodes design parameters. Binary chromosomes use 0s and 1s, while real-valued chromosomes use numbers for dimensions, angles, or material properties.

The population is evaluated together, and better solutions receive higher "fitness" scores based on how well they meet objectives and constraints. GAs are part of the broader family of evolutionary algorithms, all of which improve solutions iteratively using selection and variation.

Why Use Genetic algorithms in Engineering?

Genetic algorithms (GAs) are ideal for solving engineering problems that traditional, gradient-based methods struggle with. They work well when design spaces are complex, discontinuous, or involve many choices.

1.No Derivatives Required

Gradient-based methods rely on smooth, differentiable functions to calculate improvements. Many real-world problems don’t behave this way:

- Discrete choices like material selection or component count.

- Sudden changes in performance when designs cross physical thresholds.

- Black-box simulations where derivatives are unavailable.

GAs evaluate solutions directly, without needing derivatives, making them flexible for a wider range of problems.

2. Handle Nonlinear and Constrained Problems

Engineering problems often involve:

- Nonlinear relationships between variables and performance.

- Multiple local optima where traditional methods get stuck.

- Complex constraints that create fragmented feasible regions.

By maintaining a diverse population of solutions, GAs explore the design space globally, improving the chances of finding high-performing designs.

3.Efficient Search of Large Spaces

Some problems are too large for exhaustive search,for example, a design with 20 continuous variables and 10 discrete options. GAs focus computational effort on promising regions while keeping enough diversity to avoid premature convergence.

Applications include:

- Aerospace component design balancing weight, strength, and cost.

- Manufacturing scheduling and process optimization.

- Structural topology optimization for material placement and efficiency.

For more on how optimization integrates with aerospace workflows, see our guide on quantum-inspired optimization in aerospace and defense.

How Genetic Algorithms Work?

Genetic algorithms (GAs) solve problems by mimicking natural selection and evolution. They improve solutions over multiple generations through a cycle of selection, recombination, mutation, and evaluation.

1. Population and Representation

The algorithm begins with a population of candidate solutions. Each solution is encoded as a “chromosome” representing design parameters:

Encoding Methods

The encoding determines how genetic operators (crossover, mutation) manipulate solutions and affects search effectiveness.

2. Selection

Fitter solutions those with better objective scores are more likely to reproduce. Common selection methods include:

- Roulette Wheel: Probability proportional to fitness.

- Tournament: Random groups compete; the best moves forward.

- Rank-Based: Selection based on ranking, not absolute value.

This ensures improvement while keeping some diversity.

3. Crossover (Recombination)

Crossover combines traits from two parent solutions to create offspring:

- Single-Point: Swap segments at one point.

- Multi-Point: Swap at multiple points.

- Uniform: Randomly pick each gene from either parent.

It combines good traits, potentially producing better offspring than either parent.

4. Mutation

Mutation introduces small random changes to prevent premature convergence:

- Binary chromosomes flip bits (0→1 or 1→0).

- Real-valued chromosomes get slight perturbations.

It keeps the population diverse and explores new regions of the design space.

5. Fitness Evaluation and Iteration

Each generation, solutions are evaluated for fitness using:

- Analytical calculations

- Simulations (FEA, CFD, system dynamics)

- Physical testing

The best solutions reproduce, and the process repeats until a quality threshold is met, a set number of generations is reached, or improvements plateau.

Convergence can take dozens to thousands of generations depending on problem complexity and population size.

Key Variants and Operators in Genetic Algorithms

GA performance depends heavily on operator choices and problem formulation.

1. Fitness Functions and Constraints

Fitness functions convert engineering objectives into numerical scores. For example, minimizing weight while staying under stress limits:

Fitness = 1 / (Weight + Penalty × max(0, Stress - Limit))

Constraint handling methods include:

- Penalty Methods: Add extra cost when constraints are violated.

- Repair Functions: Adjust infeasible solutions to make them valid.

- Death Penalties: Discard invalid solutions entirely.

Poorly designed fitness functions can mislead the GA, causing it to optimize the wrong outcome.

2. Encoding and Genetic Representation

Binary Encoding: Traditional method but can create “Hamming cliffs,” where nearby values differ drastically.

Real-Valued Encoding: Better for continuous variables; usually converges faster.

Hybrid Encoding: For mixed discrete and continuous variables, applying appropriate operators to each type.

3. Operator Choices and Selection Methods

- Selection Pressure: Strong pressure speeds convergence but risks losing diversity; weak pressure preserves diversity but slows progress.

- Crossover Rates: High (0.8–0.95) focuses on exploiting existing good solutions; lower rates encourage exploration.

- Mutation Rates: Typically 1–5% of genes; too high destroys good solutions, too low risks premature convergence.

- Adaptive GAs: Automatically adjust mutation and crossover based on population diversity and convergence.

Engineering Applications of Genetic Algorithms

GAs solve diverse optimization challenges across engineering disciplines.

1. Structural and Mechanical Design

GAs help determine where to place material to maximize stiffness and minimize weight. They excel when gradient-based methods fail, especially with discontinuous feasible regions.

- Aircraft components: balance weight and structural integrity

- Automotive chassis: optimize for crash safety and lightness

- Bridge trusses: minimize cost while meeting load requirements

2. Scheduling and Resource Allocation

GAs efficiently assign jobs to machines, sequence operations, and minimize completion times under complex constraints. They handle large-scale discrete scheduling better than traditional integer programming.

3. Control and System Optimization

GAs tune PID controllers or optimize complex control systems, exploring sensitive parameter spaces without needing smooth functions. They balance multiple objectives like settling time, overshoot, and disturbance rejection.

4. Vehicle Routing and Logistics

GAs solve routing problems with factorially growing options, evolving sequences that minimize distance or time while respecting capacity, time windows, and priorities. They scale to hundreds of stops where exact algorithms struggle.

For more on simulation-driven optimization in complex systems, visit our article on simulation-driven optimization in digital mission engineering.

How BQP Supports Genetic Algorithm-Driven Optimization?

BQP integrates genetic algorithms into simulation workflows, automating setup and accelerating convergence.

The platform handles GA implementation details so engineers focus on problem formulation and results:

- Built-in GA solvers with configurable selection, crossover, and mutation operators no custom coding required.

- Automated population management tracking fitness evolution across generations with real-time visualization.

- Integration with physics simulations evaluating fitness through FEA, CFD, or system dynamics models connected to the optimization loop.

- Pareto front visualization for multi-objective problems, displaying trade-offs between competing objectives.

- Hybrid optimization combining GAs with gradient-based methods or quantum-inspired solvers for faster convergence on specific problem structures.

- Surrogate model integration reduces simulation cost by training fast approximations of expensive evaluations, then using GAs to explore the surrogate space.

With BQP, design teams efficiently test and evolve candidate designs reducing manual setup and speeding convergence on engineering objectives.

The platform's real-time tracking reveals when populations converge, when diversity drops dangerously low, and when fitness improvements stall, guiding decisions about when to adjust parameters or accept current solutions.

Learn more about where optimization and advanced simulation converge in our article on the future of aerospace with quantum-inspired simulation.

See how BQP accelerates engineering optimization pipelines. Book a Demo.

Challenges and Limitations of Genetic Algorithms

GAs are powerful but not universal solutions.

- Premature Convergence

Populations can lose diversity too early, settling in local optima instead of the best solution. Low mutation or overly strong selection often causes this. - Complex Parameter Tuning

Population size, crossover and mutation rates, and selection pressure interact in complex ways. Optimal settings depend on the problem, and adaptive GAs add extra complexity. - High Computational Cost

Evaluating large populations over many generations requires thousands of calculations. For simulation-heavy problems, GAs can be slow unless paired with surrogate models or parallel computing. - No Guaranteed Optimum

Unlike some mathematical methods, GAs do not guarantee the global best solution. They reliably find good solutions but may miss better ones.

Despite these challenges, GAs remain widely adopted because their robustness and flexibility outweigh limitations for problems where alternative methods fail entirely.

Conclusion

Genetic algorithms (GAs) help solve tough engineering problems by copying how nature evolves. Groups of candidate solutions improve over time through selection, crossover, and mutation without needing smooth functions or derivatives.

GAs work well when traditional methods struggle like with designs that are discontinuous, have yes/no choices, conflicting goals, or complex constraints. They are useful in structural design, scheduling, control systems, and logistics, especially when testing every option is impossible.

To succeed, engineers need clear problem definitions, careful parameter settings, and the understanding that GAs find good solutions efficiently, but not always the perfect one. Combining GAs with other methods or surrogate models usually gives even better results.

Explore how BQP makes optimized engineering decisions faster with integrated genetic algorithm workflows. Book a Demo.

FAQs

1. What types of problems are genetic algorithms best suited for?

GAs work best for optimization problems with large discrete or mixed-integer design spaces, multiple local optima, nonlinear or discontinuous objective functions, and complex constraints. They're particularly effective when gradient information is unavailable or unreliable.

2. How do genetic algorithms differ from gradient-based optimization?

Gradient-based methods use derivative information to follow local improvements toward optima. GAs use population-based search without derivatives, making them more robust for non-smooth problems but typically requiring more function evaluations.

3. What is the role of the fitness function in genetic algorithms?

The fitness function quantifies solution quality by evaluating how well each candidate satisfies objectives and constraints. It guides selection pressure, better fitness means higher reproduction probability and determines what the GA ultimately optimizes.

4. How do you choose population size and mutation rate?

Population size typically scales with problem complexity starting with 5-10 times the number of design variables. Mutation rates usually range from 0.01-0.05. Monitor convergence and diversity metrics to adjust parameters based on actual performance.

5. Can genetic algorithms guarantee finding the global optimum?

No. GAs are heuristic methods that find good solutions reliably but provide no mathematical guarantee of global optimality. They're appropriate when finding very good solutions efficiently is more valuable than guaranteed optimality with potentially prohibitive computational cost.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)